Mikel Donahue is the new president of Cowboy Artists of America, which has a concise mission to authentically preserve the culture of Western life in fine art as all his predecessors have done. The CAA held its first exhibition in 1967. Next year the group will celebrate its 60th anniversary. Donahue has been a member since 2016. “I didn’t know I was up for nomination,” he recalls. “I got a phone call telling me I had been voted in. I hung up the phone and sat in disbelief. It’s by far the highest honor I’ve ever had.”

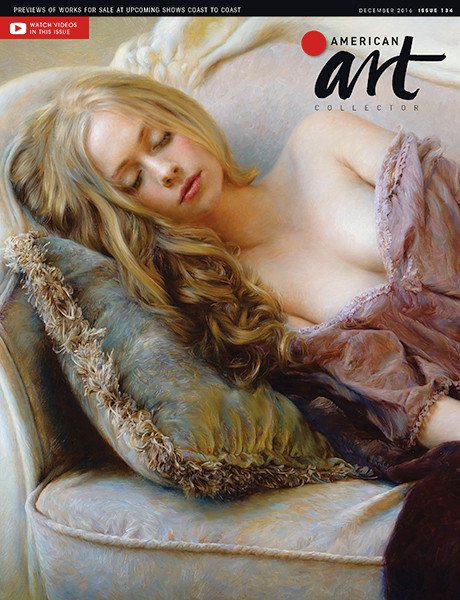

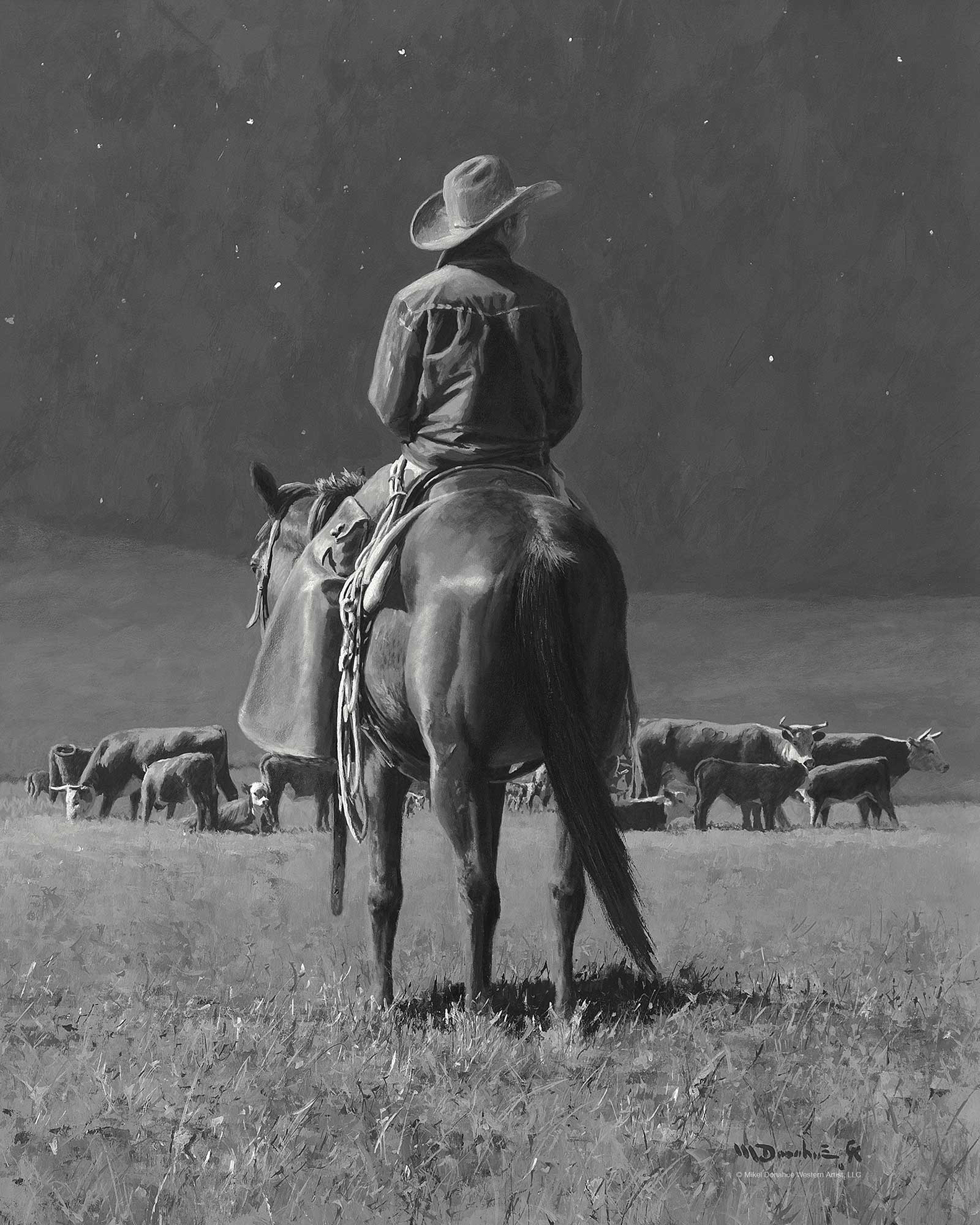

Night Riders, acrylic, 20 x 30 in.

Night Riders, acrylic, 20 x 30 in.One of the CAA’s objectives is to perpetuate the memory and culture of the Old West as typified by the late Frederic Remington, Charles Russell, and others.

Donahue was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and had extraordinary grandfathers. His paternal grandfather raised cattle in north central Oklahoma. Donahue worked with him on the ranch every summer. His maternal grandfather introduced him to the art of the West—especially Remington and Russell—on frequent visits to the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa and what was then the National Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City (now the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum).

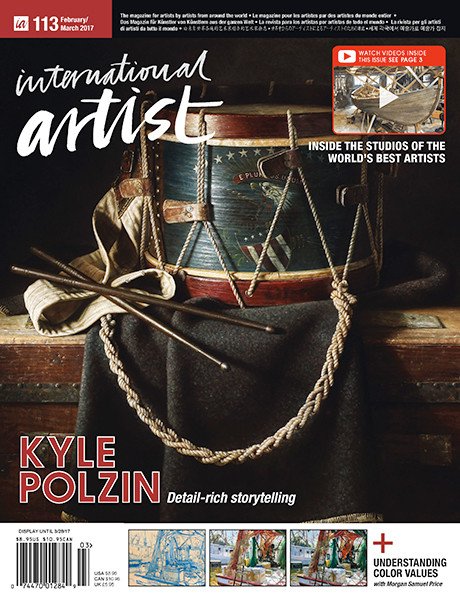

Ropin’ a Wild One, acrylic, 24 x 38½ in.

Ropin’ a Wild One, acrylic, 24 x 38½ in. “My mother’s father painted,” he relates. “He did a lot of what I call hobby painting and sold and traded his pieces. He is who initially exposed me to Western art. Dad’s father ranched and raised wheat. When I was at the ranch and around the cattle, I got to play cowboy. When I was 9 or 10, I would sit at the kitchen table and draw grandpa’s horses and cattle. Then I thought how cool it would be to draw and raise horses. It only took me 50 years to get there!”

Donahue had a 30-year career in commercial design that helped him perfect his sense of composition and to understand the principles of design and form. “Composition can make or break a piece,” he says. “I admired the vibrant color and compositions of Remington and Russell. They told stories of the West, as they were, of cowboys and Native Americans.

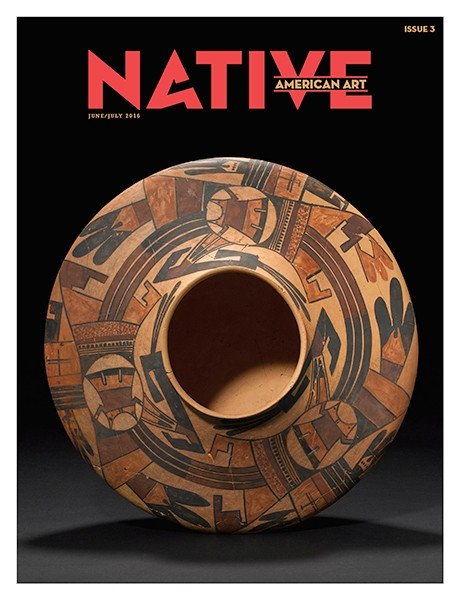

Watchful Eyes, mixed media, 22 x 30 in.

Watchful Eyes, mixed media, 22 x 30 in.

Moonlight Ladies, acrylic, 14½ x 18 in.

“Charlie Russell was a cowboy. He knew all about that life. He also knew the Native American tribes in his area and spent time among them. Understanding and knowing your subjects adds so much to a canvas. I’ve always felt in my drawing or painting you can’t do anything if you don’t know your subject. If you want to draw a horse, observe them, touch and feel a horse, study their anatomy, get to know that they have personalities.”

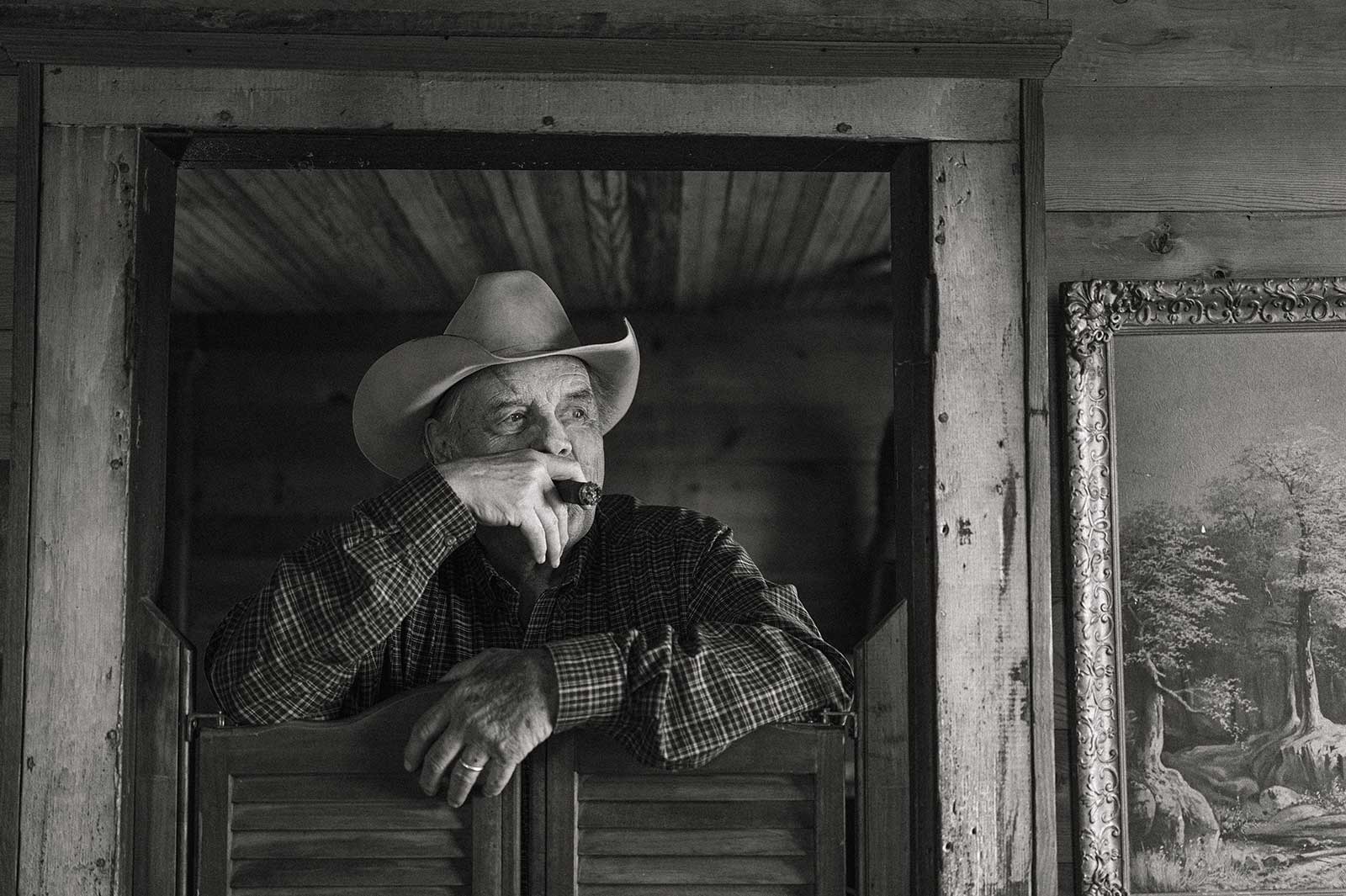

Mikel Donahue’s studio.

Several years ago I included Donahue’s mixed media drawing For Want of a Nail in the introduction to a special section devoted to horses. The work’s detail and depiction of light are extraordinary. His painting of the same subject is even more stunning. “I think the idea has some validity,” he explains. “I wasn’t looking for a great branding picture. I was looking for that day-to-day tasks, those little tedious things you have to take care of.”

Mikel Donahue in Texas during the 2025 CA trail ride. Photo by Ben Christensen.

For Want of a Nail, oil, 22 x 16½ in.

Having ranched and been around horses, he knows those daily things that make the work easier. His output isn’t bucking broncos or rodeos but, rather, depictions of the everyday life of the cowboy. Horses need to have their hooves trimmed and their shoes replaced—often every four to six weeks. A key element of the procedure is the farrier’s positioning and the horse that assures the comfort and safety of both.

There is an old proverb, “For Want of a Nail”:

For want of a nail the shoe was lost.

For want of a shoe the horse was lost.

For want of a horse the rider was lost.

For want of a rider the message was lost.

For want of a message the battle was lost.

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost.

And all for the want of a horseshoe nail.

Donahue relates how Russell portrays the warm, late-afternoon light in the West and Remington “took the harsh, midday sun and created incredible shadows.” His own depiction of the low angle of sunlight is shown in his painting Watchful Eyes. He went three or four times to an exhibition at the Gilcrease of Remington’s nocturnes, which Remington called “moonlights.” “You can’t describe them,” he says. “You have to see them in person. That work, to me, is the epitome of painting. He had no cameras, just observation. I would go out on full-moon nights looking at horses and the grass and thought, ‘One of these days I have to try it.’ I did a piece for CA and was happy with it and I’ve been hooked on it ever since. Everything is very subtle. The light is the catalyst.” Night Ridersis one of his many paintings of the light of night.

Spirit of Reverence, mixed media, acrylic and colored pencil, 13½ x 22 in.

All of Donahue’s life experiences from drawing at his grandparents’ kitchen table, working on the ranch, being in commercial design when drawing everything by hand was the process until it was eclipsed by the computer, to raising horses with his wife Christie…all of it comes together in his work. He calls it “A labor love.” —

Powered by Froala Editor