Cowboys are often portrayed as these solemn and stoic figures that are larger-than-life creatures who have passed beyond mortality into legend and then myth. This is a pleasing image, one that comes up frequently in art—the honorable cowboy. And yet, it is only part of the story.

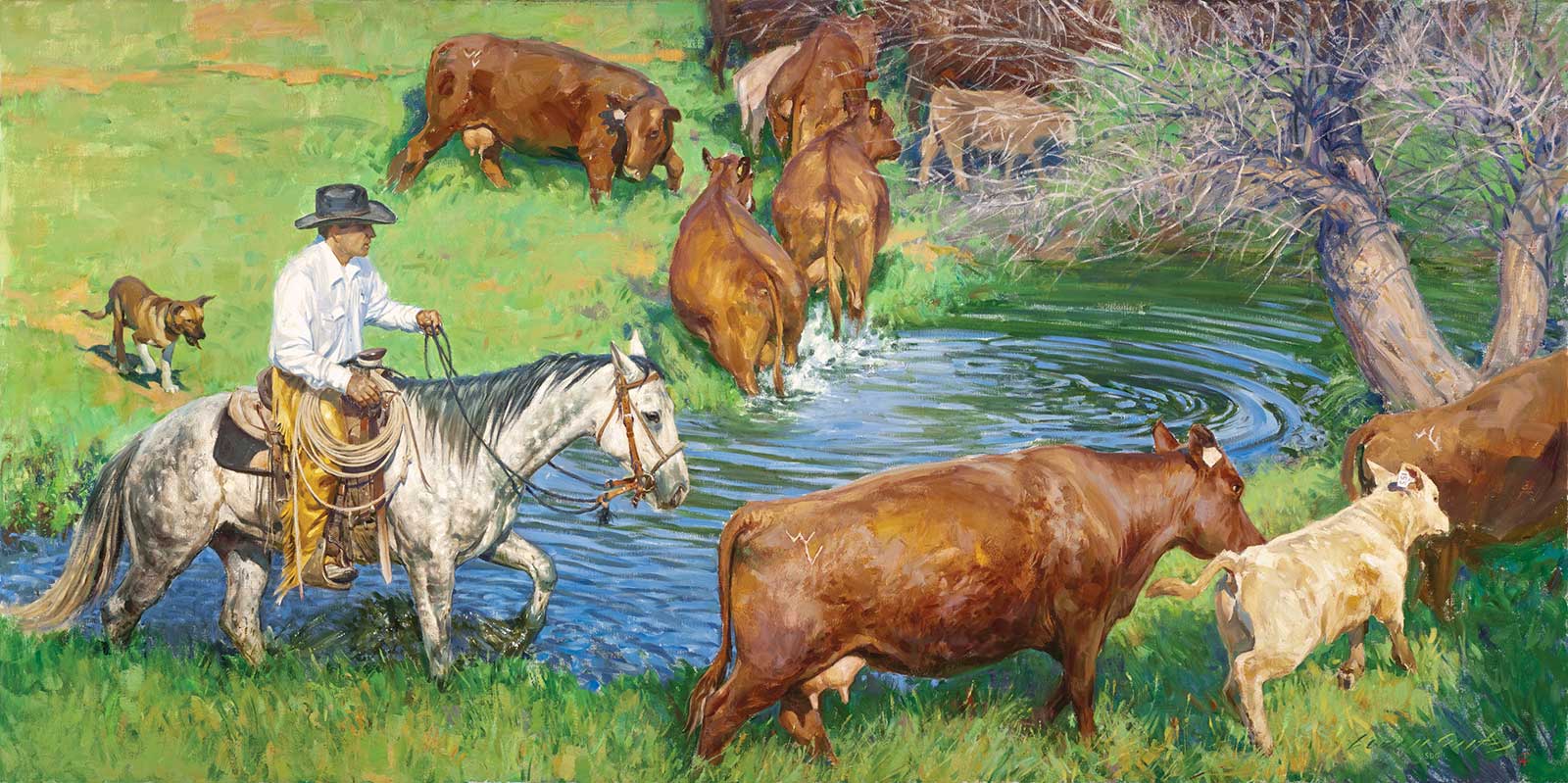

Loren Entz (1949-2022), Workin the Shallows, Nate Wald, Wald Ranch, Lodge Grass, MT, oil on canvas, 36 x 72 in.

Loren Entz (1949-2022), Workin the Shallows, Nate Wald, Wald Ranch, Lodge Grass, MT, oil on canvas, 36 x 72 in. Consider the early days of cowboying in the rough-and-tumble Old West days, when cowboys were not the clean-cut heroes of a Tom Ryan painting, their heads bowed in prayer, a coarse word having never crossed their lips. In the early days, many of the people who worked cattle on horseback were those who felt rejected by modern society, or were doing everything they could to escape it. They were known to be criminals, outlaws, grifters and rejects. Many of them went West to ride hard trails for miserable pay in dangerous conditions.

Sculptor Frank Polk captured some of these cowboys in his book F-F-F-Frank Polk: An Uncommonly Frank Autobiography. Polk, who incorporated his famous stutter into the title of his book, wrote openly about cowboys fighting, drinking and visiting whorehouses after long rides in rugged Arizona country. There was no apology in Polk’s writing—he was just stating the truth that he knew.

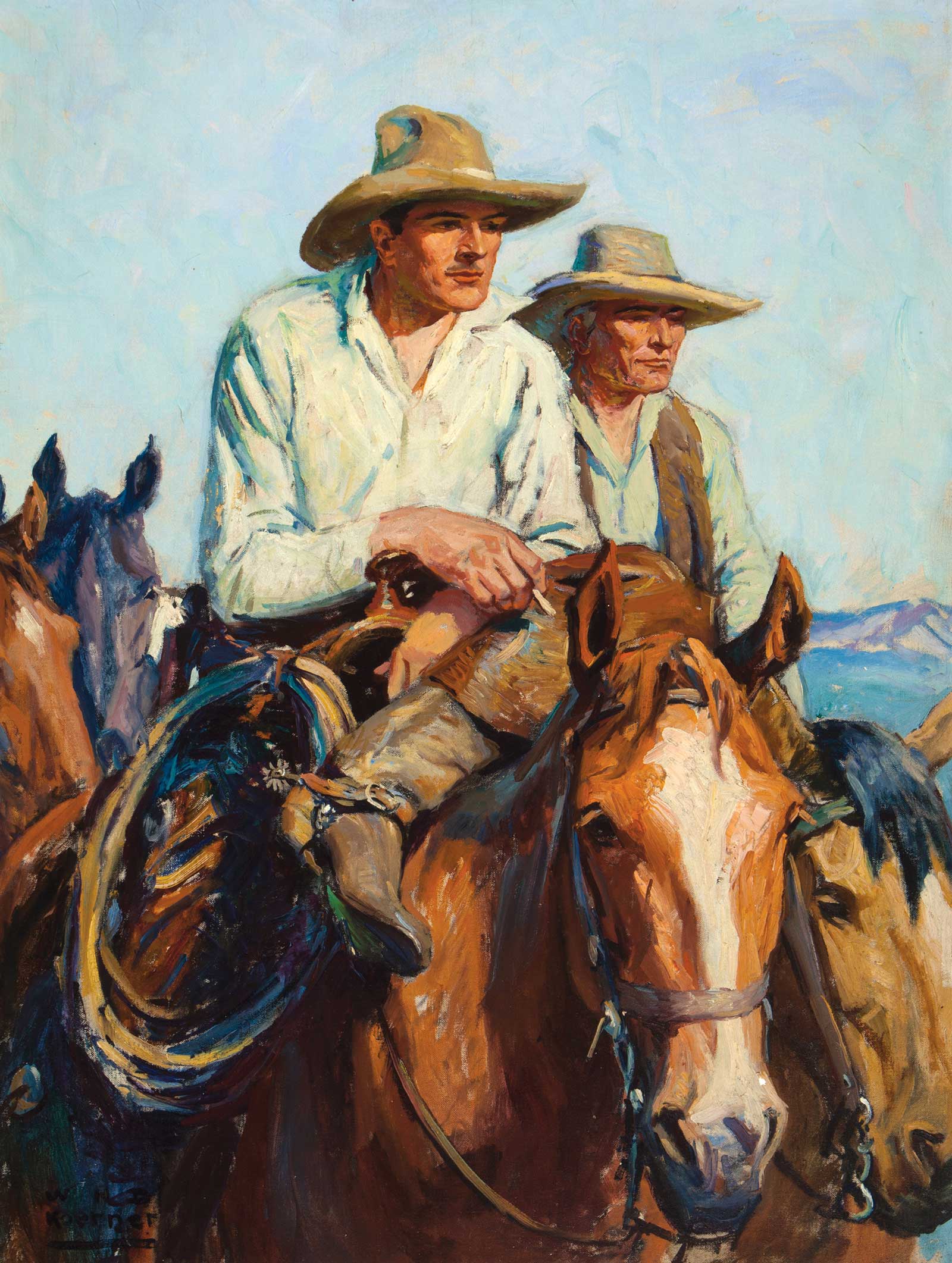

James Reynolds (1926-2010), Coming to Town, oil on canvas, 28 x 40 in.

“Well, I saddled up a horse an’ rode down there about 30 miles down to their camp. I rode into that camp, an’ that was the goldurnest thing I ever did see. All them guys had—an’ I’m tellin’ the truth—was a five-gallon keg of whiskey, a sack of jerky an’ a sack ’a flour. That’s all the commodities they had. It was a wild outfit, an’ I guess they just stayed drunk all the time. So I went up to this ol’ Les Jenkins, an’ he says to me, ‘We can’t afford to hire nobody. We’re just tryin’ to get these durn wild cattle out of here.’ So I said, ‘Well, hell, I’ll just stay down here an’ help.’ Well, we trapped a lot of cattle an’ led ’em out of there. An’ ol’ Jenkins, he got so drunk one day he fell off his horse an’ we had to go find him ’cause his horse came in without him. I’ll tell you that was just a funny doggoned outfit. I stayed with that outfit until the whiskey ran out, an’ later I’d tell the story on ’em—that all they had in the world was a five-gallon keg of whiskey, a sack of jerky an’ a sack of flour!”

Cowboys, like all humans, come in every shade of personality and disposition. And this is reflected in Western art, where the myth of the cowboy sometimes delightfully collides with the reality of the cowboy. Consider three works here: James Reynolds’ Coming to Town, which shows cowboys ready to cause havoc as they leave rough country behind for some much needed time off; W.H.D. Koerner’s Dude Wrangler, which shows an introspective figure lost in thought amid the heat and sunlight; and Loren Entz’s Workin the Shallows, Nate Wald, Wald Ranch, Lodge Grass, MT, an image that shows the cowboy as the dedicated worker who toils in the saddle to bring cows home.

None of these portrayals is wrong, because there is truth in every depiction. And that’s what makes the cowboy such a compelling figure in American art.

W.H.D. Koerner (1878-1938), Dude Wrangler, for Saturday Evening Post interior illustration, March 10, 1934, oil on canvas, 36 x 27 in.

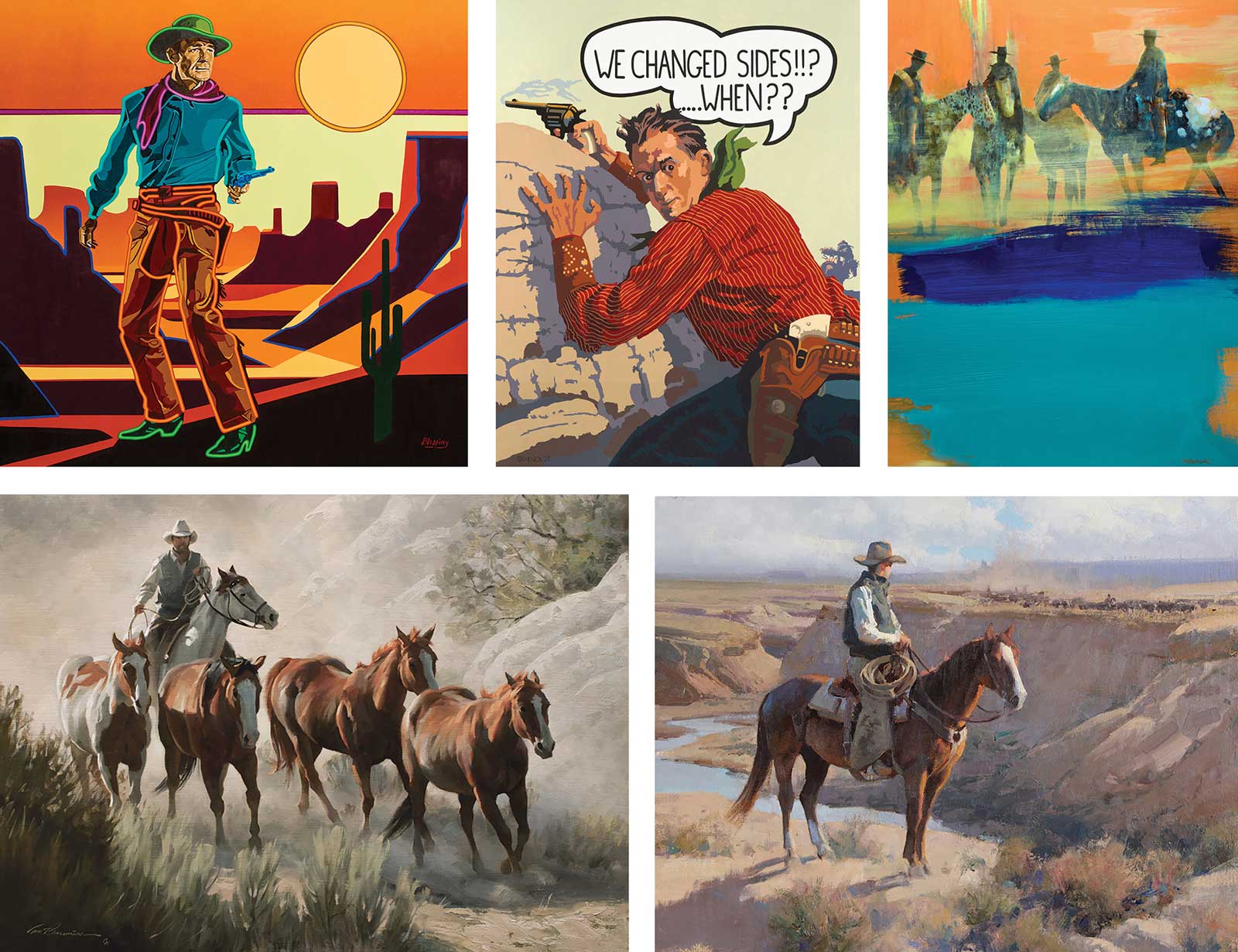

At Altamira Fine Art, the cowboy remains a timeless muse, an emblem of resilience, rebellion and reinvention. “Billy Schenck pioneered this vision, reframing cinematic cowboys through a Pop Art lens that merges myth and irony,” says gallery director Kimberly Duncan. “Rocky Hawkins channels the same spirit through gestural abstraction, dissolving the frontier into raw energy and emotion. Michael Blessing captures the contemporary cowboy through luminous color and cinematic light, honoring Western grit while revealing its modern complexity. Together, these artists bridge tradition and modernity, proving that the cowboy endures not as a relic of the past, but as a living symbol of independence and artistry in the American psyche.”

When collecting cowboy art today, Duncan suggests “looking beyond the hat and horse and instead seek the idea. The most compelling works reinterpret the myth, revealing the West’s evolving identity through color, form and concept. Collect pieces that challenge convention while honoring authenticity, that balance storytelling with innovation. In doing so, you’ll own not just a symbol of the West, but a piece of its ongoing evolution.”

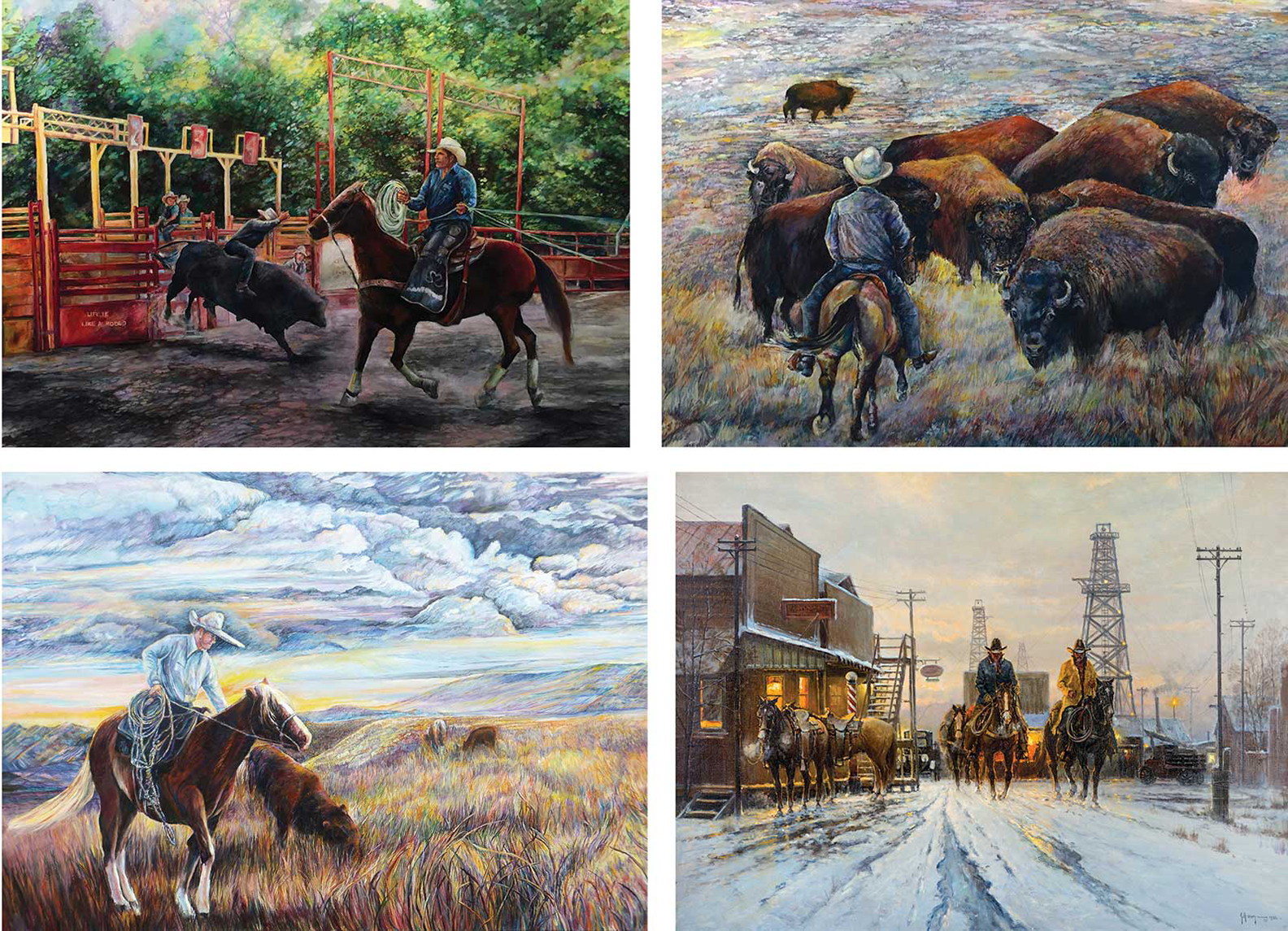

Top: Altamira Fine Art, When the Primary Hideout Turns Secondary, oil on linen, 40 x 40 in., by Michael Blessing; Altamira Fine Art, We Changed Sides?, oil on canvas, 45 x 35 in., by Billy Schenck; Altamira Fine Art, Posse, acrylic on panel, 48 x 36 in., by Rocky Hawkins. Bottom: Legacy Gallery Santa Fe, Bunchin the Mares, oil, 22 x 30 in., by Tom Browning; Legacy Gallery Santa Fe, A Drive Along the Rim, oil on linen, 20 x 24 in., by Bill Anton.

Over at Legacy Gallery Santa Fe are compelling cowboy artworks from the likes of Scott Tallman Powers, who draws inspiration from diverse cultures worldwide, as well as his local surroundings. The human element is central to his artistic journey, with people, places and experiences weaving into his creations. Tom Browning began drawing horses, wildlife and Native Americans at age 7. After five decades of painting and studying the work of Charlie Russell, James Reynolds and Haddon Sundblom, Browning never tires of finding exciting ways to express this subject matter with the colorful and fluid brushwork that distinguish his place in the Western art market.”

Legacy Gallery also features the work of Bill Anton, who is known for his depictions of the cowboy lifestyle. He was inspired by Western painting when he attended a Cowboy Artists of America exhibition in the late 1970s at the Phoenix Art Museum. In 1982, he turned to art full time, and visiting ranches in Flagstaff and Prescott, he rode in roundups and learned to work with cattle. He also developed a love of plein air painting and was much inspired by the work of Anders Zorn, Edgar Payne and Frank Tenney Johnson.

Top: Legacy Gallery Santa Fe, The Old Ways, oil, 30 x 24 in., by Scott Tallman Powers; Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery, Spring on the Scene, oil on panel, 40 x 30 in., by GL Richardson; Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery, By the Light of the Moon, oil, 24 x 36 in., by John Moyers. Bottom: Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery, Sunset Silhouette, oil on canvas, oil, 24 x 36 in., by Ed Mell (1942-2024); Gallery Wild, Rendezvous Buck Twenty Four.0, acrylic and gold leaf on canvas, 40 x 40 in., by Carrie Wild.

Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery is also known for its cowboy imagery, as is the case for GL Richardson’s Spring on the Scene. “Richardson’s experience on a New Mexican ranch adds credibility to the figurative scenes he likes to paint,” says Charles Sublette, gallery co-owner. “Enhancing the figures with fading and dissolving themes gives his work a dynamic edge within the genre.”

Cowboys are one of John Moyers’ favorite subject matters, specifically the Mexican vaquero. “Moyers, who collects Mexican blankets and costumes, makes sure that the cowboys he portrays are dressed in authentic regalia for the time frame and setting,” Sublette continues. “By the Light of the Moon is an excellent example of Moyers at his best.

Lastly, we find Ed Mell’s Sunset Silhouette, one piece from a series of cowboy’s breaking horses that the artist started painting in 1981. “Mell’s cowboys would ultimately find places in monotypes, lithographs, bronzes and oils,” says Mark Sublette, gallery co-owner. “This particular painting, and his bronze Upward,have a similar sensibility of the moment when man and horse are one. And of course, in Mell fashion, a lovely sunset is required.”

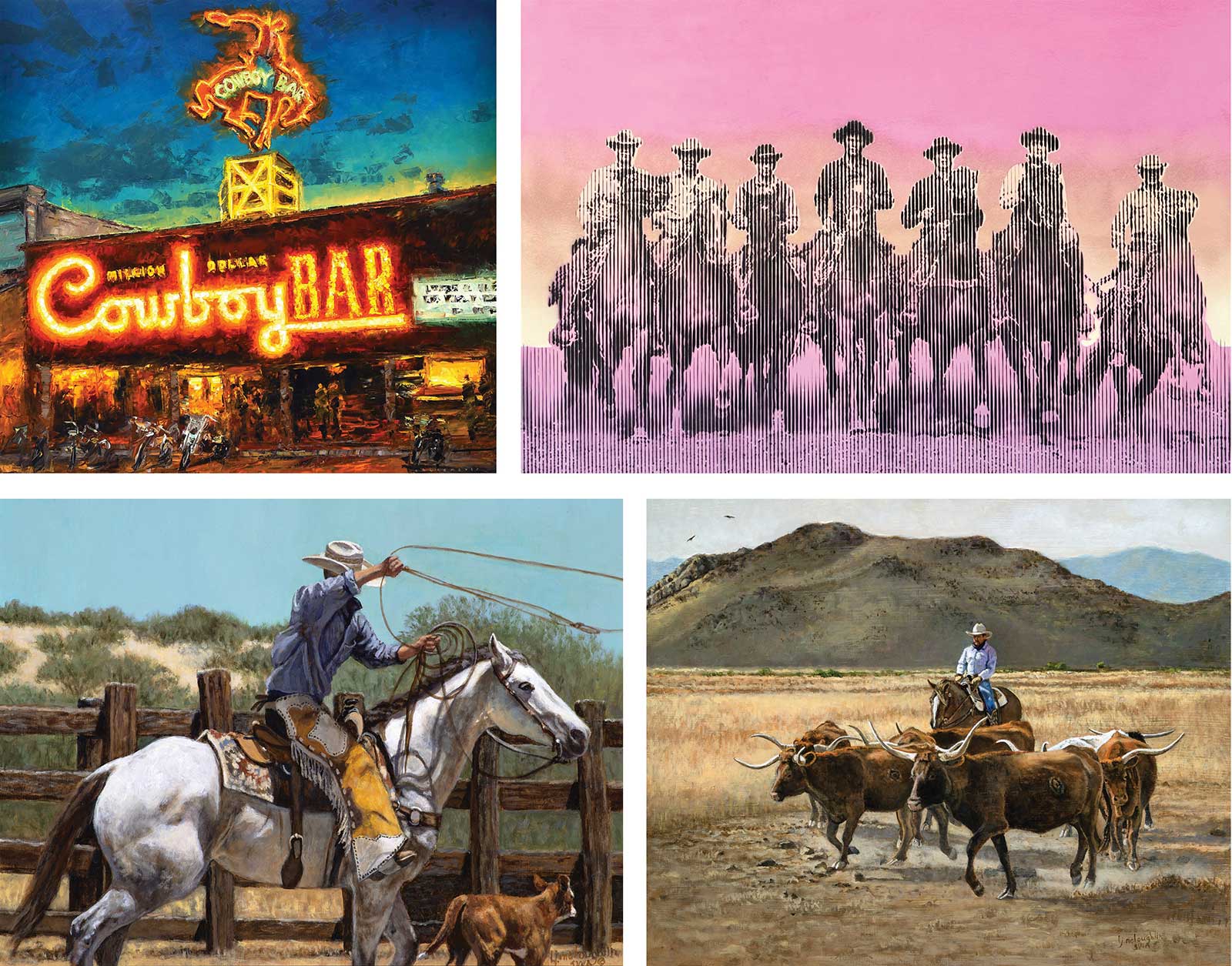

Top: Gallery Wild, Good Times, oil on canvas, 60 x 60 in., by Caleb Meyer; Gallery Wild, Mag. 7, spray paint on panel, 30 x 48 in., by Rudi Broschofsky. Bottom: LJ McLoughlin, The Catch, acrylic on Masonite, 12 x 16 in. LJ McLoughlin, Where the Longhorns Grow, acrylic on Masonite, 16 x 20 in.

Cowboy imagery at Gallery Wild channels the raw spirit of the American West: rugged landscapes, solitary riders and the tethered tension between human and wild. Each piece draws inspiration from authentic life, including silent dawns on open plains, weather-beaten steeds, the gleam of spurs at dusk, and the unspoken stories written in dust trails.

Carrie Wild’s dynamic study of horses distills motion into pure line and energy. Her brushwork speaks to the unspoken bond between cowboy and horse—a dance of trust, rhythm and power. Caleb Meyer’s vivid oil painting of Jackson’s famed Million Dollar Cowboy Bar glows like a beacon of Western nightlife, where tradition meets celebration. In contrast, Rudi Broschofsky’s super-modern take of Mag. 7,rendered in a hand-cut stencil and gradients of pink spray-paint, bridges nostalgia and pop sensibility, reframing the mythic cowboy for a contemporary audience.

Top: Paulette Bensignor, Life Lessons, oil on canvas, 30 x 48 in.; Paulette Bensignor, Refusing to Move, oil on canvas, 24 x 30 in. Bottom: Paulette Bensignor, Rider Wearing Sombrero, oil on canvas, 30 x 40 in.; J Watson Fine Art, Rawhide and Roughnecks, oil on canvas, 36 x 48 in., by G. Harvey (1933-2017).

“For collectors, cowboy art isn’t merely decorative, it’s cultural storytelling,” says Abigail Mitchell, gallery manager. “Seek works that balance authenticity and innovation, that echo both the grit and romance of the West. Whether through expressive linework, glowing palette knife strokes or conceptual abstraction, each piece reminds us that the cowboy’s legacy lives on—not just in history, but in the living language of art.”

J Watson Fine Art is known for its diverse selection of original paintings. Representatives at the gallery love to help collectors locate the perfect piece at a price they are happy with. The gallery is also superb at arranging commissions with many of its award-winning artists. As for cowboy imagery, the gallery boasts wonderful examples such as G. Harvey’s (1933-2017) Rawhide and Roughnecks. “Harvey was a brilliant American artist,” says Joanne Watson, gallery owner. “His rustic Western paintings with their wonderful depiction of cowboy life and nature are prized by collectors. Born in Texas, he studied the day-to-day life of cowboys and shares an authentic portrayal of them through his paintings.”

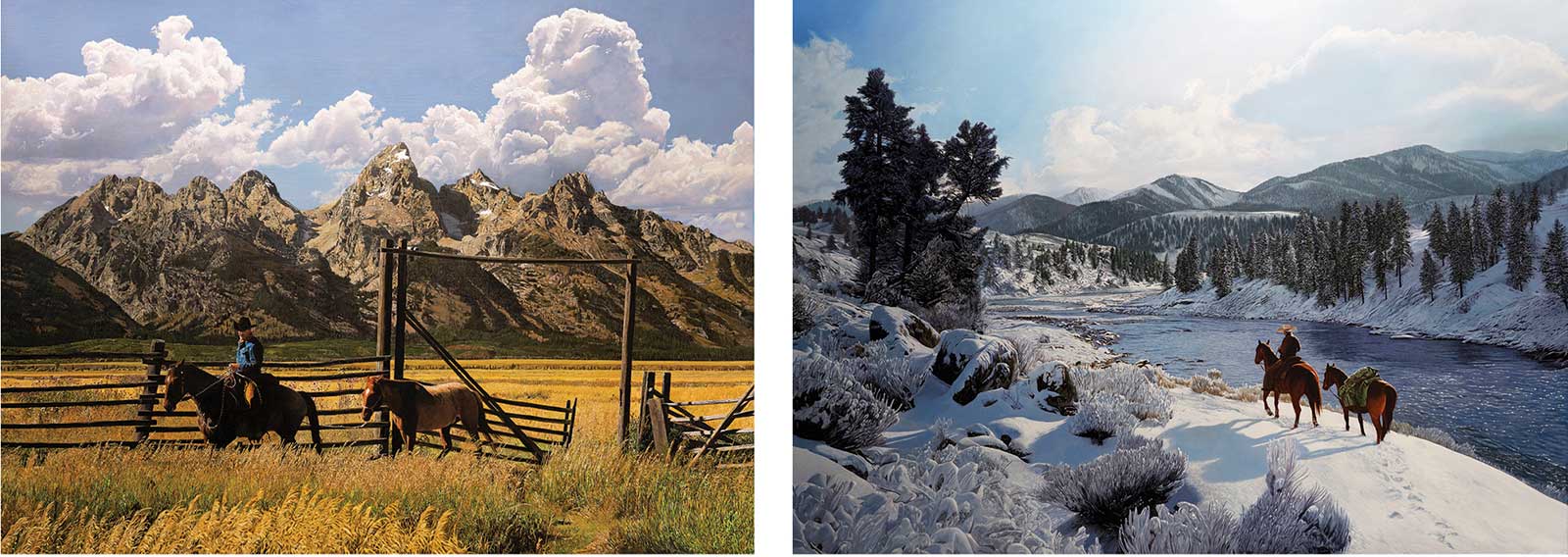

J Watson also offers John Bye’s oil pieces Teton Dreams and Winter in the West. “When creating a Western painting, I depict the real aspects of the Western landscape and the cowboys that work within it,” the artist shares. “My paintings are inspired by the rugged and often hard terrain the cowboy travels through, whilst also showing the beauty of the landscapes and the gentle strength of the bond between horse and rider.”

J Watson Fine Art has showrooms in Van Nuys, California, and Stevensville, Montana, by appointment.

J Watson Fine Art, Teton Dreams, oil on canvas, 30 x 40 in., by John Bye; J Watson Fine Art, Winter in the West, oil on canvas, 30 x 40 in., by John Bye.

LJ McLoughlin is an artist and a working cowgirl. “Ranch life is just a part of what I do every day,” she says. “My inspiration comes from the Southwestern landscape I’m surrounded by—historical working ranches with cowhands doing what they enjoy the most, and the beautiful, true connection between horse and man, to get a job done. I have years of experiencing ranch life, breaking out and riding horses, rubbing elbows with incredible human beings whose lives need to be recorded with paint and brush, lest we forget the quiet isolation, beauty and grit of the ‘cowboy’ way.”

Artist Stephanie Campos recently completed her charcoal work Nellie Brown, who was an icon of the American West. “She used hand-braided reins called mecates(Spanish for horsehair rope),” Campos explains of her subject. “They were often a blend of black-and-white horse-tail hair and a traditional part of vaquero culture in the 18th and 19th centuries. Mecates are tied into the headstall and serve as both a rein and a lead rope.”

Stephanie Campos, Nellie Brown, charcoal on Stonehenge archival paper, 13 x 10½ in.

Artist Paulette Bensignor continues her search to better understand people, with Western subjects being her primary muse. “I am interested in observing and recording people’s relationship to their environment,” she adds. “These current paintings, such as Life Lessons, Refusing to Move and Rider Wearing Sombrero, are based on my memories of pretending I was a cowgirl riding the plains and participating in rodeos.”

Bensignor continues, “Being a cowboy or cowgirl is a serious life choice. It involves a person who is hard working, brave, adheres to membership rules and is skilled. The responsibilities are caring for oneself plus caring for large animals, who can kill you or die from injury or disease. My paintings are not only for entertaining my viewers, but for exploring the Western lifestyle. My art represents preserving the spirit of the West and the connection to American identity.” —

Featured Artists & Galleries

Altamira Fine Art

172 Center Street, Suite 100 Jackson, WY 83001

(307) 739-4700, www.altamiraart.com

Paulette Bensignor

info@pbensignor.com

www.pbensignor.com

IG: @pbensignor

Stephanie Campos

artist@stephaniecampos.com

www.stephaniecampos.com

Gallery Wild

80 W. Broadway, Jackson Hole, WY 83001

(307) 203-2322, www.gallerywild.com

J Watson Fine Art

(661) 476-7558

info@jwatsonfineart.com

www.jwatsonfineart.com

Legacy Gallery

225 Canyon Road, Santa Fe, NM 87501

(505) 986-9833, www.legacygallery.com

Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery

6872 E. Sunrise Drive, Suite 130

Tucson, Arizona 85750

(520) 722-7798

www.medicinemangallery.com

L J McLoughlin

(520) 507-0213

www.ljmcloughlin.com

Powered by Froala Editor